Know About “Behavior Driven Development (BDD)”

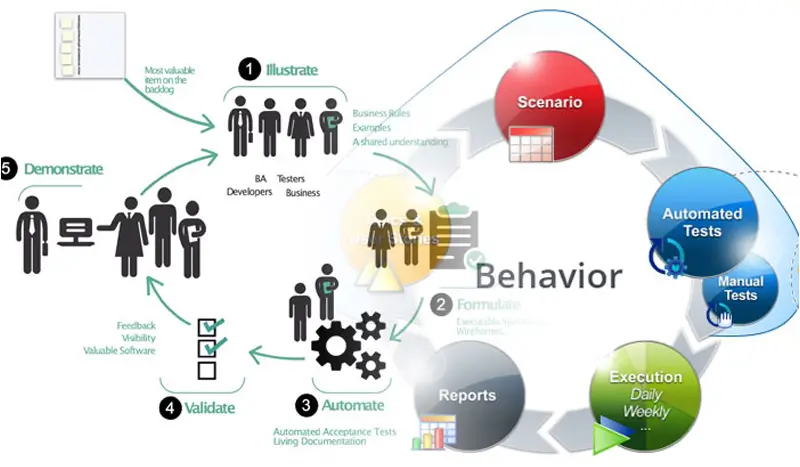

Behavior Driven Development (BDD) is a strategy for creating programming through continuous example-based communication between developers, QAs and BAs.

The basic role of BDD technique is to enhance communication among the stakeholders of the project with the goal that each component is effectively comprehended by all members of the team before development process begins. This helps to identify key scenarios for every story and furthermore to eradicate ambiguities from requirements.

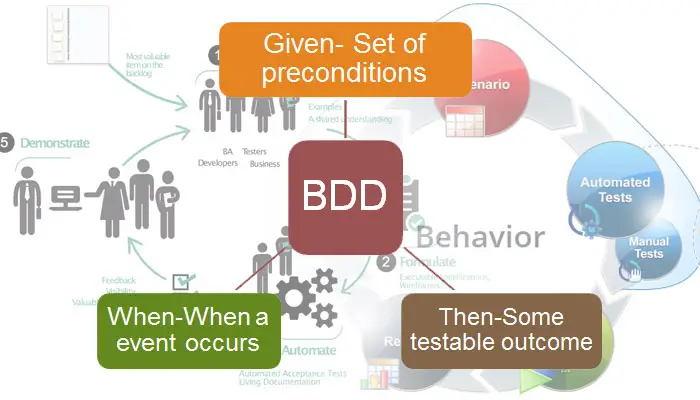

In BDD, Examples are called Scenarios. Scenarios are organized around the Context-Action-Outcome pattern and are written in a special format called Gherkin. The scenarios are a method for explaining (in plain English) how a given element ought to act in various circumstances or with different input parameters. Since Gherkin is structural, it serves both as a specification and input into automated tests, thus the name “Executable Specifications”.

Behavior Driven Development was developed by Dan North as a response to the issues like:

- Where to start the process?

- What to test and what not to test?

- What to call the tests?

- How to understand why a test fails?

Best Practices (Good Behavior)

Keep in mind, behavior situations are more than tests – they additionally speak to requirements and acceptance criteria. Great Gherkin originates from great behavior.

Phrasing Steps

Compose all steps in third-person perspective. On the off chance that first-person & third-person advances blend and situations wind up confusing, simply utilize third-person at all times.

Compose steps as a subject-predicate action phrase. It might entice to let parts of peech out of a step line for brevity, particularly when utilizing Ands and Buts, yet incomplete expressions make steps ambiguous and more likely to be reused improperly.

How about we consider a test that looks for pictures of pandas on Google. Underneath would be a sensible test method:

Feature: Google Searching

Scenario: Google search result page elements

- Given the user navigates to the Google home page

When the user entered “panda” at the search bar

Then the results page shows links related to “panda”

And image links for “panda”

And video links for “panda”

The last two “And” steps come up short regarding subject-predicate phrase format. Are the links meant to be subjects, implying that did they play out some meant? Or would they say they are meant to be direct objects, implying that they receive some action? Composing steps without a clear subject and predicate is not only poor English but poor communication.

Additionally, utilize fitting tense for each sort of step. Givens ought to dependably utilize present or present perfect tense, Whens and Thens ought to dependably utilize present tense. The Given step above demonstrates an action when it says, “The user navigates.” Actions always implies the exercises of behavior. Be that as it may, given steps are intended to build up an initial state, not exercise a behavior. Utilizing present or present perfect tense shows a state rather than an action.

The correct example will look like this:

Feature: Google Searching

Scenario: Simple Google search

- Given a web browser is at the Google home page

When the user enters “panda” into the search bar

Then links related to “panda” are shown on the results page

And keep on mind, all steps are written in third-person.

Better Titles

Good titles are considered as great steps. The title resembles the essence of a situation – it’s the primary thing people read. It must convey in one compact line what the behavior is. Titles are regularly logged by the automation framework too.

Choices

Another normal misguided judgment for amateurs is feeling that Gherkin has an “Or” step for conditional or combinatorial logic. People may assume that Gherkin has “Or” on the grounds that it has “And”, or maybe programmers need to treat Gherkin like an structured language. Be that as it may, Gherkin does not have an “Or” step. Whenever automated, each step is executed consecutively.

The following is a bad example based on ax classic Super Mario video game, showing how people might want to use “Or”:

Feature: SNES Mario Controls

Scenario: Mario jumps

- Given a level is started

When the player pushes the “A” button

Or the player pushes the “B” button

Then Mario jumps straight up

Clearly, the author’s wanted to present that Mario should jump when the player pushes either of the two buttons. The author intent to cover multiple variations of the same behavior. In order to do it on right terms, use Scenario Outline sections to cover multiple variations of the same behavior, as shown below:

Feature: SNES Mario Controls

Scenario Outline: Mario jumps

- Given a level is started

When the player pushes the “

Then Mario jumps straight up

Examples: Buttons

- | letter |

- | A |

- | B |

Known Unknowns

Test data can be hard to deal with. Some of the time, it might be possible to seed data in the system and compose tests to reference it, however in other time, it may not. Google search is the prime example: the data list or result list will change as both Google and the Internet change. To deal with the known unknown, compose situations protectively so changes in the underlying data do not cause test runs to fail. Besides, to be really behavior-driven, consider data not as test information but rather as examples of behavior.

Consider the following example from the previous post:

Feature: Google Searching

Scenario: Simple Google search

- Given a web browser is on the Google page

When the search phrase “panda” is entered

Then results for “panda” are shown

And the following related results are shown

| related |

| Panda Express |

| giant panda |

| panda videos |

This situation utilizes a step table to unequivocally name results that appear to show up for a search. The step with the table would be executed to repeat over the table sections and check each showed up in the result list. Notwithstanding, imagine a scenario where Panda Express were to leave business and subsequently never again be positioned as high in the outcomes. (We strongly expect not.) The trial would then fail, not on the grounds that the search feature is broken, but rather in light of the fact that a hard-coded variation ended up invalid. It is smarter to compose a stage that all the more cleverly confirmed that each returned outcome by one way or another identified with the search query, like this way: “And links related to ‘panda’ are shown on the results page.” The step definition execution could utilize standard articulation parsing to check the presence of “panda” in each result link.

Another decent element of Gherkin is that step definitions can conceal information in the automation when it shouldn’t be uncovered. Step definitions may likewise pass data to future steps in the automation. For example, consider another Google search scenario:

Feature: Google Searching

Scenario: Search result linking

- Given Google search results for “panda” are shown

When the user clicks the first result link

Then the page for the chosen result link is displayed

Just take a notice how the When step does not explicitly name the value of the result link – in simple way it says to click on the first one. As the time passes by the value of the first link may change, but there will always be a first link. In order to successfully verify the outcome, the Then step must know something about the chosen link, but it can simply reference it as “the chosen result link”.

Data Handling

Some kind of test data should be handled directly within the ground of Gherkin, but other types must not. Keep on mind that BDD is specification by example – scenarios should be descriptive of the behaviors they cover, and any data composed into the Gherkin should support that descriptive nature.

Less Is Better

Scenarios should be short and sweet. It is frequently favored that scenarios should content a single-digit step count (<10). Long scenarios are complicated to understand, and they are often symbolic of poor practices. One such complication is writing imperative steps instead of declarative steps.

Imperative steps define the mechanism of how an action should happen. They are highly procedure-driven. For example, consider the following When steps for entering a Google search:

- When the user scrolls the mouse to the search bar

- And the user clicks the search bar

- And the user types the letter “p”

- And the user types the letter “a”

- And the user types the letter “n”

- And the user types the letter “d”

- And the user types the letter “a”

- And the user types the ENTER key

The granularity of actions may appear needlessly excess, yet it shows the point that imperative steps center particularly around how actions are taken. Along these lines, they regularly require numerous steps to completely achieve the intended behavior. Besides, the intended behavior is not always as self-documented as with declarative steps.

Declarative steps imply what action ought to occur without giving the majority of the data to how it will occur. They are behavior-driven on the grounds that they express action at a higher level. The majority of the imperative steps in the example above could be written in one line: “When the user enters ‘panda’ at the search bar.” The scrolling and key stroking is inferred, and it will at last be taken care of by the automation in the step definition. When attempting to reduce step count, inquire yourself as to whether your steps can be written more decoratively.

Another explanation behind lengthy scenarios is scenario outline misuse. Scenario outline make it very simple to add pointless rows and columns to their Examples tables. Pointless rows squander test execution time. Additional columns indicate complexity. Both should be avoided. Below are questions to ask yourself when facing an over sized scenario outline:

- Does each row represent an equivalence class of variations?

- For example, searching for “elephant” in addition to “panda” does not add much test value.

- Does every combination of inputs need to be covered?

- N columns with M inputs each generates MN possible combinations.

- Consider making each input appear only once, regardless of combination.

- Do any columns represent separate behaviors?

- This may be true if columns are never referenced together in the same step.

- If so, consider splitting apart the scenario outline by column.

- Does the feature file reader need to explicitly know all of the data?

- Consider hiding some of the data in step definitions.

- Some data may be derivable from other data.

These questions are meant to be sanity checks, not hard-and-fast rules. The main point is that scenario outlines should focus on one behavior and use only the necessary variations.

Structure and Style

While style often takes a backseat during code review, it is a factor that differentiates good feature files from great feature files. In a truly behavior-driven team, non-technical stakeholders will rely upon feature files just as much as the engineers. Good writing style improves communication, and good communication skills are more than just resume fluff.

Below are a number of titbits for good style and structure:

- 1. Focus a feature on customer needs.

2. Limit one feature per feature file. This makes it easy to find features.

3. Limit the number of scenarios per feature. Nobody wants a thousand-line feature file. A good measure is a dozen scenarios per feature.

4. Limit the number of steps per scenario to less than ten.

5. Limit the character length of each step. Common limits are 80-120 characters.

6. Use proper spelling.

7. Use proper grammar.

8. Capitalize Gherkin keywords.

9. Capitalize the first word in titles.

10. Do not capitalize words in the step phrases unless they are proper nouns.

11. Do not use punctuation (specifically periods and commas) at the end of step phrases.

12. Use single spaces between words.

13. Indent the content beneath every section header.

14. Separate features and scenarios by two blank lines.

15. Separate examples tables by 1 blank line.

16. Do not separate steps within a scenario by blank lines.

17. Space table delimiter pipes (“|”) evenly.

18. Adopt a standard set of tag names. Avoid duplicates.

19. Write all tag names in lowercase, and use hyphens (“-“) to separate words.

20. Limit the length of tag names.

Without these rules, you might end up with something like this:

Feature: Google Searching

@AUTOMATE @Automated @automation @Sprint32GoogleSearchFeature

Scenario outline: GOOGLE STUFF

- Given a Web Browser is on the Google page,

when The seach phrase “

Then “

and The related results include “related”.

Examples: animals

- | phrase | related |

| panda | Panda Express |

| elephant | elephant Man |

Guidelines

- 1- Clarify in the feature file what the feature is about, soon after the “Feature:” before continuing to the situations (preferably in “In order/As a/I want” format).

- Don’t make reference to UI components

- Don’t make reference to ‘click’ or different actions connected to explicit UI components

- The scenario ought to stay legitimate if the UI is replaced with another UI tomorrow

- Avoid extremely point by point steps where possible ((helps to focus and avoid clutter)

2- Write high-level scenario steps by raising the level of abstraction and spotlight on the “what” instead of the “how”

Write scenarios using business language rather than using technical language so that it can be understood by everyone.

3- Write down the scenarios from the point of view of the person who will utilize or needs the feature (not generally a member or user). Use ‘I’ and clarify who the ‘I’ is in ‘Given’ step.

4- Each and each scenario should be independent, i.e. scenarios ought not rely upon different scenarios or data created by different scenarios.

5- Don’t make reference to features or actions which are not related to the actual feature under test.

Example: Scenario is to check the balance is displayed currently in a user account. Before checking the balance, user needs to login to check the balance but Login is not part of the check balance scenario.

6- Use Scenario Outline when you have many scenarios that pursue the very same pattern of steps, just with different input values or expected results.

7- Scenario Outline examples should be easy to understand. Column names should be meaningful (e.g. | Contact Method | Enquiry Type | instead of | value1 | value2 | ), so that the steps are understandable.

8- Scenarios need to be environment independent.

9- Write scenarios for testing happy paths and important error cases.

10- Avoid typos and always use grammatically correct English.

Recommendations

- 1. Wherever possible steps should be reused. This can also be achieved by

- parameterizing (if applicable)

- keeping it short and simple

- Actions like login should be handled part of Background or hooks.

- Setup and teardown should be part of hooks and should not be part of the scenario.

2. Whenever a feature or behaviour changes the existing scenarios needs to be updated (from a latest branch in TFS)

3. Actions, which are not directly related to the scenario should be handled outside the actual scenario:

For more information about Behavior Driven Development Test Automation please drop an e-mail at – info@oditeksolutions.com